This month I’ve observed not just a continued ramping up of commentary and positivity on clean energy technology/ project / policy activity – but also more measured caution that ‘clean’ technologies may not be as clean as they seem, or not the ‘right’ technologies to meet set goals. Or they may be. To know which though, you’d need to do your own research (DYOR). Some more on this below. Plus:

- Are we seeing a renaissance in Operational Research?

- Does that rooftop solar PV quote makes sense? (Warning: May contain Monte-Carlo simulation)

- Opportunities for island communities

Streams of Commentary

If the phone, computer or TV is switched on then it’s difficult to escape the stream of news headlines, invites to webinars, links to Youtube videos and other shared media of all sorts of types relating to the energy transition. There’s lots of commentary. And lots of commentary on the commentary. But what about original / informed thoughts and actions?

There is a huge amount of ground-breaking and collaborative academic & industry work on the go at the moment directed at decarbonising everything from steel plants and power stations to cars and cookers. Much of this has been in development for years or even decades, but the mood now is that urgent action is needed on many fronts to dig ourselves out of 2020 and save the planet. November saw – amongst other things – Wales Climate Week, which rattled through a diverse agenda of excellent industry and public talks, including the latest on Welsh marine and hydrogen developments, and closer to home the Blue Skies Conference discussed ambitious plans to rejuvenate the Heathrow area in a post-COVID, climate-responsible way. How objective is all this action-focused work though? Are the right conclusions being drawn based on the information available?

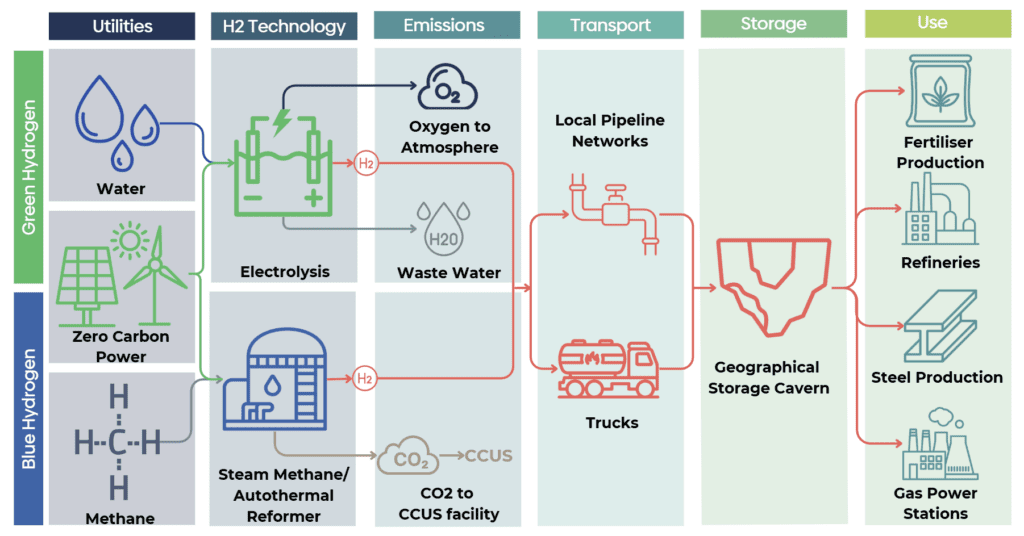

Tom Baxter gave an excellent talk to the IChemE this month on ‘Over-selling hydrogen’ a couple of weeks ago – where he questioned whether hydrogen was being over-sold for different applications by vested interests, or by commentators who’ve not done their own research. The case for hydrogen as a carbon-free fuel sounds compelling. However there are a number of applications where it just doesn’t stack up against alternative options for heat or energy storage. To delve deeper and compare the options available requires a return to chemical engineering and economic basics..

HM Government has also just unveiled its 10 Point Plan for a green industrial revolution. It is an ambitious menu of actions, timelines and funding commitments for a broad range of green growth projects, with The Top Three being offshore wind, clean hydrogen and advanced nuclear. Large sums of money have been pledged for this, but there is lots of commentary (and counter-commentary) on how much impact the money could have on such a challenge. For example: Further down the list (at #8) is Carbon Capture, Usage and Storage (CCUS), where ‘up to £1 billion‘ will be invested ‘to support the establishment of CCUS in 4 industrial clusters‘:

Except that according to our research, a small-ish (1 million tonne CO2 / year) post-combustion capture plant costs in the order £0.5bn to install, and that’s without the CO2 going anywhere. So in the world of CCUS – ‘up to £1 billion’ may not go that far towards decarbonising distributed industrial sites across the UK.

Dr. Evil contemplating the cost of a smallish carbon capture plant

The Renaissance of OR?

Despite the noise of commentary and subjective conclusions drawn by vested interests, there does seem to be a lot of actual high-quality evidence / modelling-based analysis going on behind the scenes to back up the Government’s policy formation: Just a look at this week’s job openings for the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) shows a large number of carbon capture / CO2 infrastructure / heat policy related roles looking to be filled, many of which are shown as promoted roles in LinkedIn. This seems to be a growth area – and to back this up I read a couple of weeks ago that the Government Operational Research Service (GORS) is now for the first time up to 1000 analysts:

Could it be that this esoteric, niche and geeky ‘super-discipline’ could be going mainstream? I had heard some views a few months back that OR is going through somewhat of a renaissance; maybe there is something to this after all..

Ever since I ground out the eventual completion of my MSc over the summer – and committed to applying OR techniques as part of a day-to-day smart toolkit to make better development project decisions, I’ve been wondering exactly how to break into that ecosystem at a time when most people are confined to their homes during a normal working day. A week ago I joined the OR Society’s annual Blackett Lecture – where the main talk delivered by Chris Skidmore explored the theme of OR in the 21st Century, it’s importance in the future – and the UK’s future role in global science. The talk was detailed and deep, and in some parts hard to follow, but I found the outlook for OR work to be enlightening. In some of the follow-up on-screen chat, there was one comment that caught my attention – and which I’ve paraphrased as I can’t recall the exact words:

I took this as some really valuable validation that this discipline is seen by policy-researchers as key to tackling the grand challenges of the 21st Century. And to remind me that I did actually complete that MSc in the end, here’s the proof I received from Strathclyde Business School at the start of November (although I still haven’t received the parchment):

Make Hay While the Sun Shines

Last week we had a survey and quote for solar panels. This wasn’t something that we were seriously thinking about. We hadn’t even talked about it as an idea. But when a solar installer called out of the blue and said they could install a 4kW system for £4000 it got my attention and I thought I’d find out a bit more. I’d heard that solar panel costs had become (very) cheap in the last year or so as a result of Chinese technology output, but suspected that the installation in London would still be expensive – and that overall such a project in London would be neither cheap nor particularly efficient (in terms of solar intensity).

Nonetheless, we had the basic survey to see what could be done on our terraced roof, then scrutinised the quote & technical datasheets (like only an engineer can) and feedback reviews etc – and came to the conclusion that this could be a good winter project to do. [Obviously the worst time to try to book air con / solar jobs is in the summer].. After a bit of follow-up chat it seems as though we could probably even squeeze a 5kW system up there without adding much more to the cost.

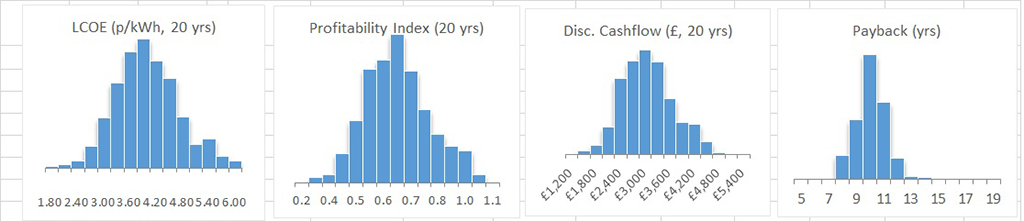

I thought this could be a good ‘real life’ mini-scale test for some of the industrial modelling we’ve been working on, so we ran it through our risked simulator to see how it looks: Our ‘risked’ stochastic simulator uses an affordable Monte-Carlo calculation engine as a way to examine the spread and likelihood of different economic outcomes. This is more useful that just doing a ‘single-point’ payback calculation, because although the installer has given us a fixed quote for the job, we don’t have much certainty at this point in time on what the average cost of importing / exporting electricity might be over the next 20 years; or precisely how much electricity will be generated from the panels each year; or how much of the electricity generated during sunlight hours will be consumed in the house (rather than exported at the lower Smart Export Guarantee rate) etc. No need to get hung up on ‘the right’ numbers to use though, when sensible-looking ranges can be easily estimated for each value instead. Just let the Monte-Carlo simulator take care of the rest.

For those not familiar: Stochastic or Monte-Carlo simulation is an established technique that works by individually simulating hundreds or thousands of random ‘alternate reality’ scenarios. The calculated random results are then aggregated, and sorted into order / counted to give the distribution of values and likelihoods. It is really useful for understanding ‘the shape of things’, and the risks associated with assumptions. This is part of the day-to-day toolkit of subsurface scientists/ engineers and commercial analysts, but I’ve never seen it used in facilities projects. I don’t know why. Anyway here’s a snapshot of the results:

Risked Rooftop Solar PV Project Indicators

The conclusion? On the face of it, the payback time at almost 10 years is pretty long, and the ‘return’ is very modest – so why bother? With a system installation cost of around £900/kW, this is well below current benchmarks and seems to be a good deal – also it is a very low risk (unlike many of the oil & gas projects we’ve worked on over the years). There didn’t seem to be any scenario where it would not pay back. So in fact, considering the 25-year performance guarantee that comes with the system, there is virtually zero risk of this not paying for itself in the medium-term.

And there’s more: We realised that once such a system is installed, there are further opportunities to reduce our electric bills, by adjusting our usage habits during sunny days (when the most electricity is being generated). For example: Putting on the dishwasher / washing machine on the way to work (or remotely through phone app) in the morning instead of in the evening.

We’re keen to move on this and the detailed survey is tomorrow.

I’ve wondered a bit about the effectiveness & payback on heat pump systems – which intuitively feels like they may not make much sense in a draughty 100-year old house (even with the £5000 Green Homes Grant). This may need to go through the Monte-Carlo simulator next month..

Opportunities for Island Communities

Many of us with links to Holyhead have been following the progress of the West Anglesey Tidal Demonstration Zone with keen interest over the last few months – and all of a sudden the Morlais Public Inquiry starts tomorrow. Having secured the lease from the Crown Estate back in 2014, this is a good reminder of the long cycles involved with maturing energy developments, even up to the point where final investment decisions can be made to award the main project contracts.

The Selkie Project ran an interesting webinar last week covering foundation & mooring designs for tidal devices – and talked about the similarities & differences between the requirements for oil & gas projects and renewables projects. I still feel there are significant similarities.

It was also announced in November that Nova Innovation have been awarded £1.2M to progress the early development studies for a 5 x 100kW tidal turbine array between Ynys Enlli (Bardsey Island) and the Llyn Peninsula. This exciting-sounding project is described as the ‘world’s first blue energy island’.

It does feel that there is more opportunity and support than ever for island communities to be self-sufficient with energy.. Closer to home, the nearest island to us at Olwg HQ in Brentford is a mere 50 metres away: Johnson’s Island, owned by the Port of London Authority, is home to a number of eclectic artist studios. I’m wondering if they’re interested in floating solar panels / canal weir turbines to make their own electric? We should have a chat with them..